A recent global synthesis on deep pelagic fish has highlighted the remarkable diversity and critical role of these species for life on Earth. Oceans hold the largest vertebrate biomass on the planet, a wealth still largely unexplored, even by scientists. These deep-dwelling species play an essential role in balancing global ecosystems and regulating the climate, according to a team of IRD marine ecologists and partners. The research is based on data gathered from oceanic expeditions conducted in various parts of the world.

The Hidden Richness of the Deep Oceans

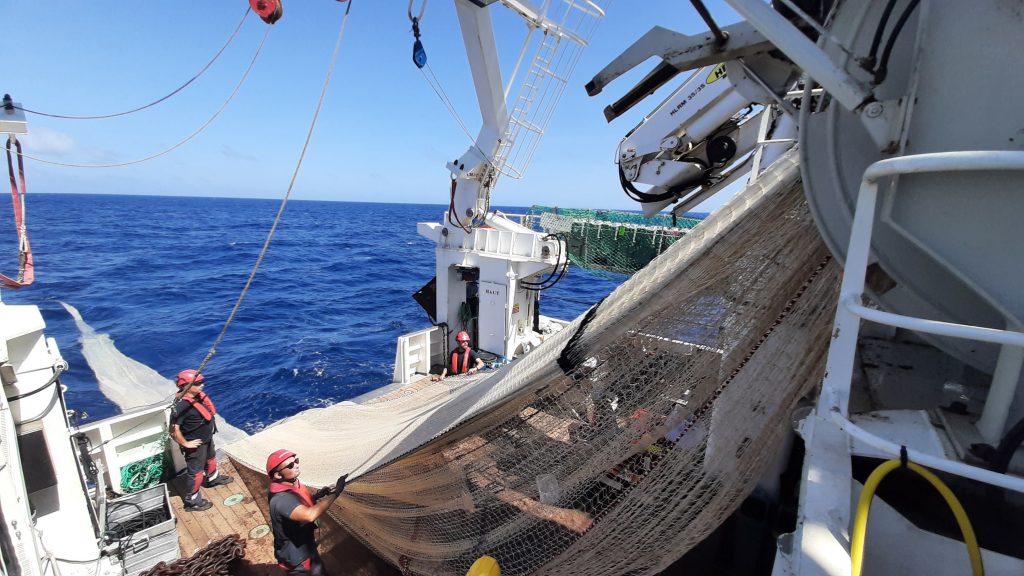

Ocean depths are often seen as homogenous, simple environments, where species could be exploited without significant consequences. However, recent studies, including campaigns by the Tropical Atlantic Interdisciplinary Laboratory (LMI) TAPIOCA off the coast of Brazil, challenge this misconception.

“Different pelagic zones have been analyzed through various disciplines, from physics to ecology, studying biodiversity at every level, from bacteria to top predators,” explains Arnaud Bertrand, marine ecologist at IRD.

Leandro Nole Eduardo, also a marine ecologist at IRD, investigated over 200 species, examining their morphologies, diets, and migrations, revealing an astonishing diversity in the depths, even greater than that of surface species.

Feeding, Defecation, and Carbon Storage

One major discovery by Leandro Nole Eduardo was the specialized feeding behaviors of these species, previously thought to be generalists due to the scarcity of food sources without photosynthesis in the depths.

“We had assumed that deep pelagic species were opportunistic feeders, consuming whatever little food was available in the absence of photosynthesis at such depths. However, we found that they are, in fact, highly specialized in their feeding methods, to reduce competition,” explains Leandro.

Some fish, for instance, use bioluminescence to hunt, while others perform vertical migrations to escape predators and feed. These migrations enable them to capture carbon at the surface, transporting it to the deep and releasing it through respiration and defecation. “The amount of carbon transported depends on the type of food: a species feeding on small crustaceans will not transport as much carbon as a predatory fish,” notes Leandro. This process contributes to the global carbon cycle, essential for climate balance.

Preserving Deep Socio-Ecosystems

These ecosystems, still poorly understood, are highly vulnerable to climate change. “We estimate a 20% loss in the biomass of deep pelagic organisms by 2100,” warns Arnaud Bertrand. Such a decline will not come without consequence, as the deep oceans are essential socio-ecosystems, both for human populations and for life on Earth. Besides the harmful effects yet to be identified, their degradation would have major implications for climate disruption, which are still not accounted for in IPCC models.

To avoid the worst, it is essential to preserve these distant yet vital spaces.